EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The value of the domestic market for pharmaceuticals is expected to grow by 4.5-5.0% in 2022 relative to the 2021 figure, thanks to the easing of fears about COVID-19 and the return of the Thai economy to somewhere close to its normal level, with the subsequent rebound in growth then feeding into stronger spending power. This has helped to encourage patients to return to hospitals and clinics as they seek treatment for health issues, resulting in greater overall demand for medicines and medical supplies. Beyond this, the reopening of the country to foreign arrivals has further boosted demand for pharmaceutical products, especially within tourist areas. Over 2023 to 2025, the market is expected to continue to grow thanks to the likely ongoing rise in incidences of chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs), the extension of universal health coverage programs to cover the whole of the Thai population, the increasing number of foreign patients seeking treatment in Thai hospitals, and the rising global concerns with wellness and preventative healthcare that are influencing Thai consumers.

However, the industry will also face challenges in the form of: (i) the country’s lack of manufacturing capacity, which means that the Thai pharmaceutical industry is highly dependent on imports; (ii) intensifying competition from new players, both Thai and international; and (iii) rising overheads, which are being driven up both by the need to overhaul and upgrade production lines to comply with the GMP-PIC/S standard, and by the greater cost of inputs. The net effect of these pressures will then be to place a limit on players’ ability to generate profits.

Research view

Over 2023 to 2025, the domestic market for pharmaceuticals is expected to grow on increasing rates of NCDs among the general population, the broader access to healthcare provided for by the Universal Coverage Scheme, the greater number of overseas patients seeking treatment in Thai hospitals, and global trends that are encouraging greater consumer interest in wellness and preventative healthcare. However, stiffening competition will limit how far operators’ profits may grow.

- Manufacturers of pharmaceuticals: Income will tend to strengthen on: (i) continuing demand for COVID-19 vaccines and medicines to treat the illness once contracted, while the relaxation of pandemic controls means that social and economic activity has returned to normal and with this, individuals are now increasingly seeking treatment in hospitals; (ii) the steady rise in rates of NCDs; (iii) the greater access to medical services provided by government welfare programs, which is underpinning growth in the volume of medicines distributed through hospitals, especially for treatments that are under patent; and (iv) the ability of manufacturers to increase distribution through pharmacies and expand export markets in the ASEAN region, where demand for medicines and vaccines remains strong.

There are some challenges in this business as follows: (i) The entrance of new players which will intensify market competition; (ii) the steadily rising cost of imported precursors; (iii) moves by the government to control the prices of medicines used in private hospitals and business, which may make it difficult for manufacturers to raise their prices; and (iv) the additional costs imposed by the need to upgrade facilities to meet the GMP-PIC/S standards, which would affect business margin.

- Distributors of pharmaceuticals (retailers and wholesalers): Income growth will be steady in the coming years, helped by: (i) increased interest in personal healthcare and preventative medicine; (ii) recovery in the tourism sector, which will bring increased footfall in pharmacies, especially in the major tourist areas; and (iii) the broadening of distribution channels to include online sales, advertising on digital media, and the development of mobile phone applications that offer health advice. However, it is also likely that players will have to contend with greater competition within their particular segment.

- Stand-alone pharmacies will likely have to contend with a worsening threat from large chain stores. For example, Fascino (a chain of pharmacies) plans to extend its network from its current total of 105 branches (as of 2020) by opening another 200 franchises by 2022, Save Drug (part of the Bangkok Hospital group) also hopes to expand its network (from current 80 stores nationwide). Pure Pharmacy (by BIG C) aims to expand additional 7 branches in 2022 from 146 branches in 2021. In addition, the range of retail sites from which pharmaceuticals are sold is broadening to include discount stores, supermarkets (of which at least 50 new branches open every year) and convenience stores (7/11 plans to open 700 new branches a year).

- Wholesalers are increasingly moving into the market space currently occupied by retail operations. They expand new distribution channels, provide promotion campaign and advertise via online media so that they can respond to customers’ needs, with the lower cost of medicines purchased as their main advantage.

OVERVIEW

The pharmaceutical sector includes conventional medicines and medical supplies which are used in the diagnosis and treatment of illnesses. Conventional pharmaceuticals can be split into two groups:

1) Original drugs or patented drugs are medicines that have gone through the lengthy research & development (R&D) process, and therefore would involve significant investment. Manufacturers of original drugs are normally given a 20-year patent[1] protection and when the patent expires, other manufacturers are then allowed to produce those medicines.

2) Generic drugs: These are drugs that are manufactured by a company that was not responsible for their development, but which begins to produce them once the patent for the original drug expires. Although they may be produced under a trademark, this will not be that of the primary manufacturer. Nevertheless, generic drugs are identical to their original counterpart in terms of active ingredients, and so their therapeutic value is likewise indistinguishable. However, because manufacturers of generics may be able to source cheaper inputs and are freed from the burden of research and development costs, generic manufacturing costs may be significantly lower than those of original drugs.

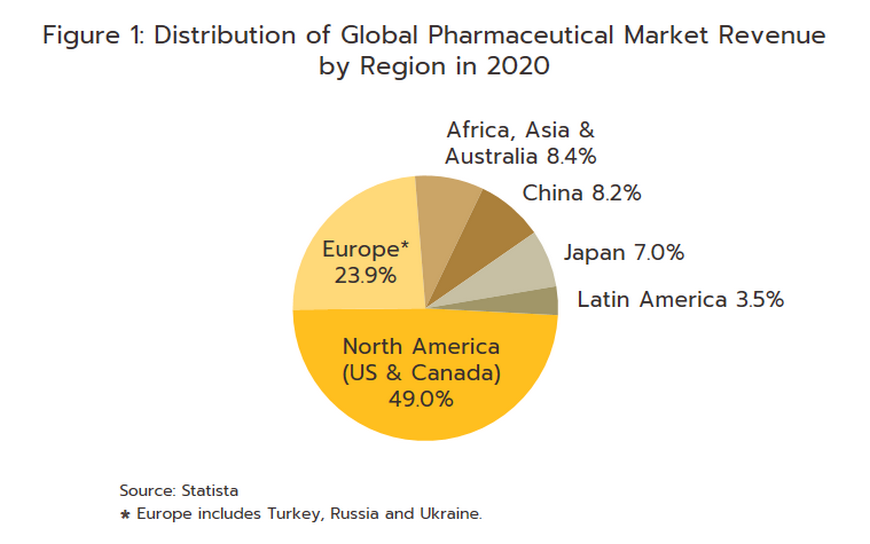

The continual and costly R&D required in the development of new medicines and medical supplies have prompted many global producers of pharmaceutical and medical supplies, especially original drugs, to cluster in developed economies such as the United States, Europe, and Japan, because of easy access to skilled professionals, expertise and manufacturing technology. These countries then export to meet global demand (Figure 1), while developing countries are left to play the role of importers of expensive patented medicines.

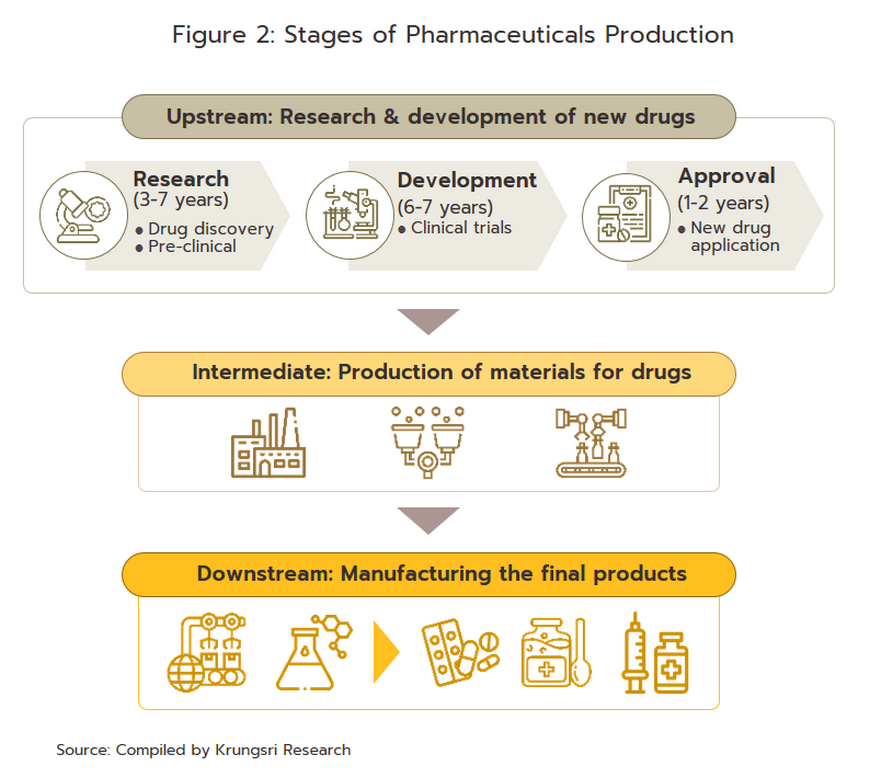

The conventional medicines production chain is split into three stages (Figure 2).

1) Primary: This involves R&D of new medicines.

2) Intermediate: This involves the production of ingredients to be combined to make the final product. These are either active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), or inactive pharmaceutical ingredients (or excipients) that are normally added to speed up chemical reaction. The ingredients manufactured in this stage are normally already available in the market but required special techniques to achieve the desired chemical reaction or to change the molecular structure of existing chemicals, which normally require advanced technology and a large investment.

3) Manufacture of finished products: This is usually a manufacturing of generic drug, and generally depends on imports since Thailand in fact sources some 90% of the inputs used in the manufacture of pharmaceuticals from abroad. These imports are then used to produce generics in the form of pills, liquids, capsules, creams, powders, and injectables. Product group with the highest value is pain medication. Most Thai players in the pharmaceuticals industry fall into this group.

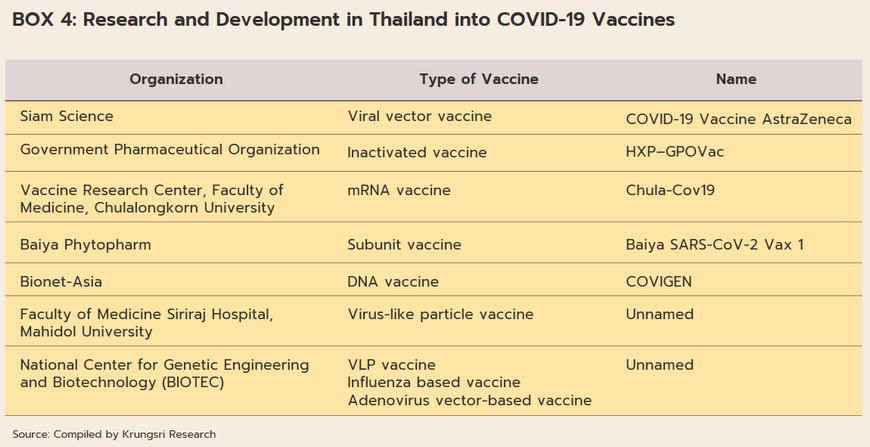

Figures from the Thai Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indicate that as of December 2021, Thailand was home to 151 pharmaceutical production facilities that met the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards, though only 8% of these were able to manufacture active pharmaceutical ingredients. Output from the latter includes products such as aluminum hydroxide, aspirin, sodium bicarbonate, and deferiprone, most of which is used as inputs into manufacturer’s own production processes. Research and development also tends to be restricted to work on vaccines (e.g., for HIV, influenza/bird flu, and most recently, for COVID-19). Thailand has in fact had a strategic national plan for vaccine development since 2005, and at present, stage two of this, which covers 2023-2027 (stage one covered 2020-2022) is being drawn up. This lays out the goal of providing for the full vaccination of the population in both normal and emergency situations, as well as expanding domestic vaccine production to a level where this can replace imports.

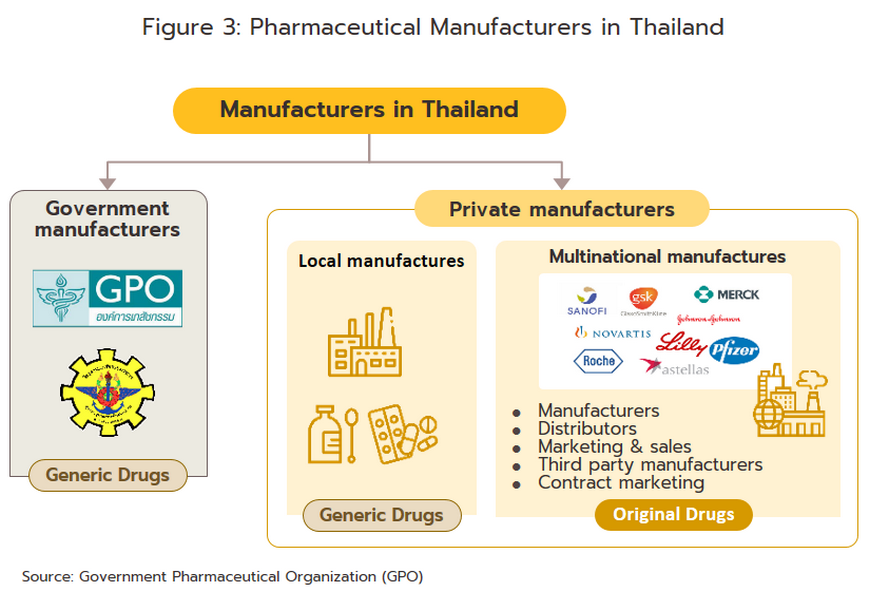

Players in the medicines sector can be split into two groups (Figure 3).

Group 1 comprises government agencies: (i) the Government Pharmaceutical Organization (GPO) as a manufacturer of original drugs and importer of high-value products, especially treatments for non-communicable diseases (e.g. cholesterol-lowering medications, diabetes); to be sold at low prices; and (ii) the Defense Pharmaceutical Factory, which emphasize the production of generic drugs as alternatives to imported drugs.

The Government Procurement and Supplies Management Act B.E. 2560 has specified GPO as an entrepreneur similar to the private producer in the sector. This created a level playing field for private enterprises and increased competition between the GPO and private sector players, including suppliers in India and China which export low-cost products.

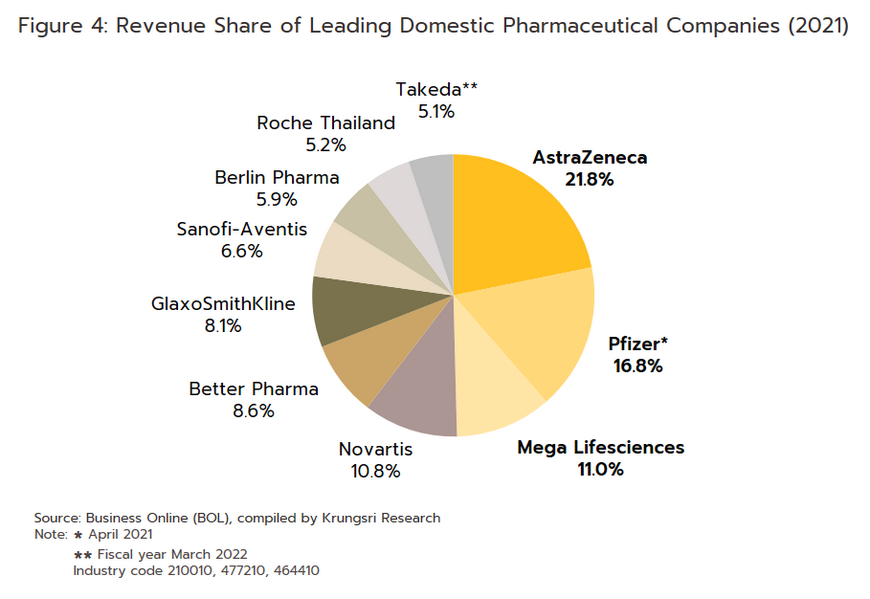

- Group 2 comprises private sector producers. This can be divided into two sub-groups: (i) local manufacturers with Thai shareholders, which typically produce general-purpose low-cost generic drugs. Examples include Siam Pharmaceuticals, Berlin Pharmaceutical Industry, Thai Nakorn Patana, Biopharm Chemicals and Siam Pharmacy. Contract manufacturers such as Biolab, Mega Lifesciences and Olic (Thailand) also belong in this group; and (ii) multinational corporations (or MNCs) with foreign shareholders, which focus on original drugs and operate as agents to import pricier drugs for distribution in Thailand, though some have also established production facilities in the country. Operators in this group include Pfizer, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis. In 2021, AstraZeneca (Thailand) had the largest share of revenues by providing COVID-19 vaccines via domestic production and imports (Figure 4).

Currently, two laws govern the manufacture of pharmaceuticals in Thailand. They are: (i) Patent Act B.E. 2522 (1979) and amendments, which grant patent-rights to discoverers and inventors (i.e. protects intellectual property rights), supervised by the Department of Intellectual Property; and (ii) Drug Act B.E. 2510 (1967) and amendments[2], which regulate the manufacture, import, sale and marketing of drugs in Thailand. In terms of regulatory bodies, the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for overseeing compliance in the sector. Its tasks include licensing operators and registering drugs for domestic distribution.

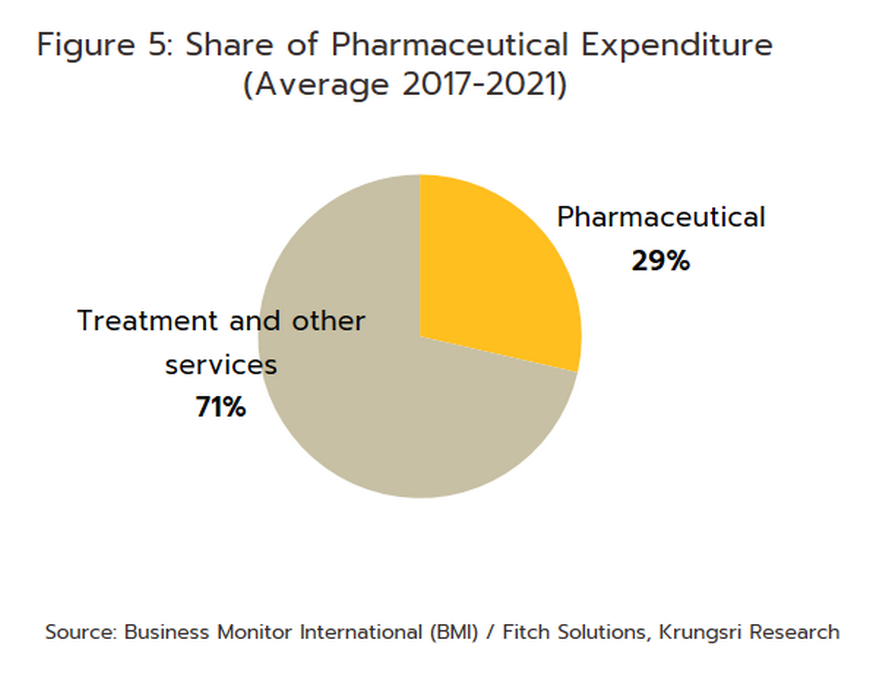

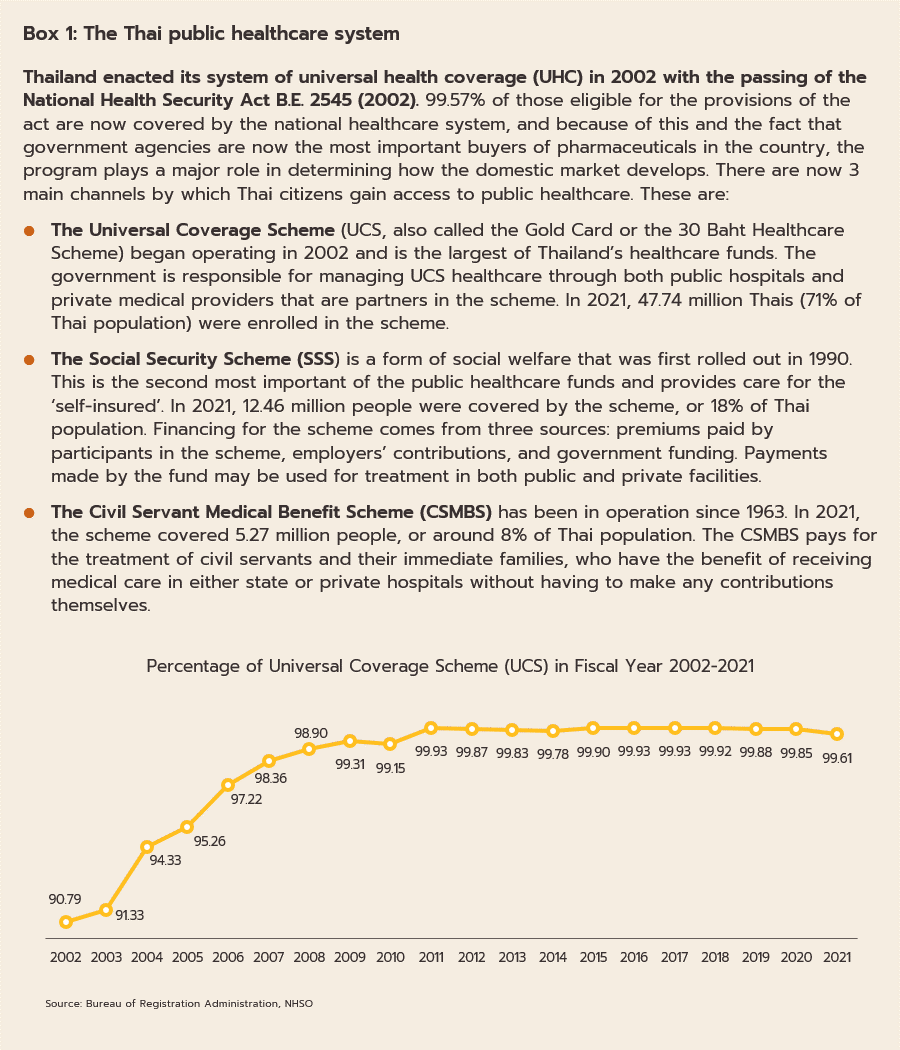

In distribution, approximately 90% of Thailand’s pharmaceuticals output is consumed by the domestic market. Drugs and medicines now account for a quarter of all domestic medical expenses (Figure 5). This was largely triggered by the expansion of national universal healthcare coverage (UHC), specifically the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) which now covers 99.61% of total eligible insured persons (Box 1) population. This has increased access to healthcare for most of the population nationwide, which naturally caused the consumption of medicines to jump (The Fiscal year 2021 budget of the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS) rose to THB 190bn, up 2.2% from the FY2020 budget).

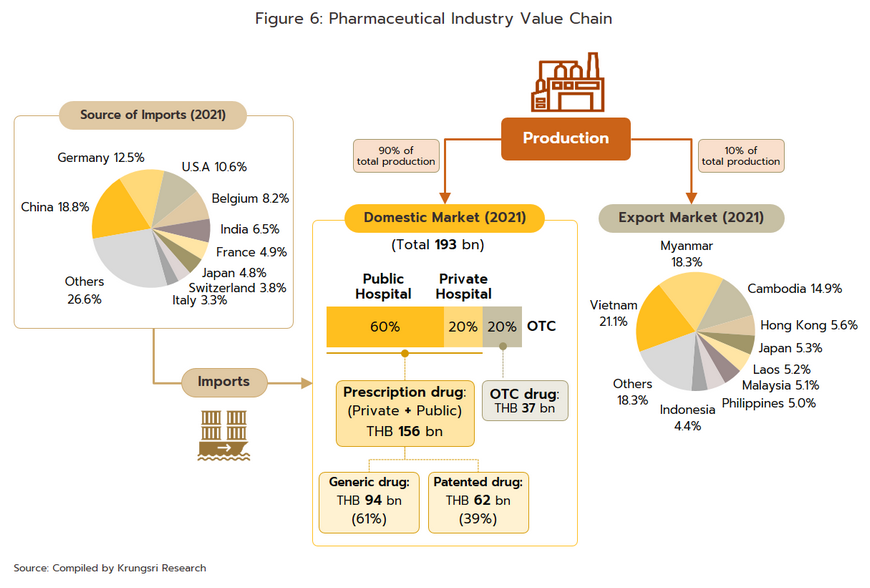

Domestic market: Medicines and pharmaceuticals are distributed through two main channels (Figure 6).

- Hospitals: Thailand’s public healthcare system is extensive, covering both civil servants and the majority of scheme claimants. By value, 80% of the total domestic market for medicines is distributed through hospitals, comprising 60% government hospitals and 20% private-sector operations. Medicines distributed through hospitals are generally prescription drugs, which can be further sub-divided into (i) generic drugs, which account for 61% of the value of medicines distributed via hospitals, and (ii) patented drugs, which make up the remaining 39%. But although this latter group has a smaller share, consumption of patented drugs is growing faster than the consumption of generic drugs, because they are mostly used to treat common chronic non-communicable conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease.

- Over-the-Counter (OTC) medicines: Although the government health insurance scheme encourages individuals to increasingly seek medical care in hospitals instead of buying OTC medicines from pharmacies, the latter remain an important distribution channel for those with common minor ailments which can be treated with a quick trip to a pharmacy. Hence, the value of the OTC drugs market has been stable at 20% share of the total market for medicines. There are 22,205 registered pharmacies[3] in Thailand (source: FDA, August 2022), 18,551 are modern pharmacies (83.5%), 19.8% of which are in Bangkok and 80.2% in the provinces. Pharmacies can be split into the two major groups: (i) stand-alone stores, mostly SMEs, which account for around 75% of modern pharmacy outlets in the country, and (ii) chain stores, which may either be run, centrally-funded, or organized for expansion through franchising, such as Fascino and Save Drug (a member of BDMS). Beyond this, modern trade outlets (including discount stores, supermarkets, convenience stores, and specialist health stores) are turning over a part of their floor space to medicines and pharmaceuticals, and so are able to reach a wide range of customers.

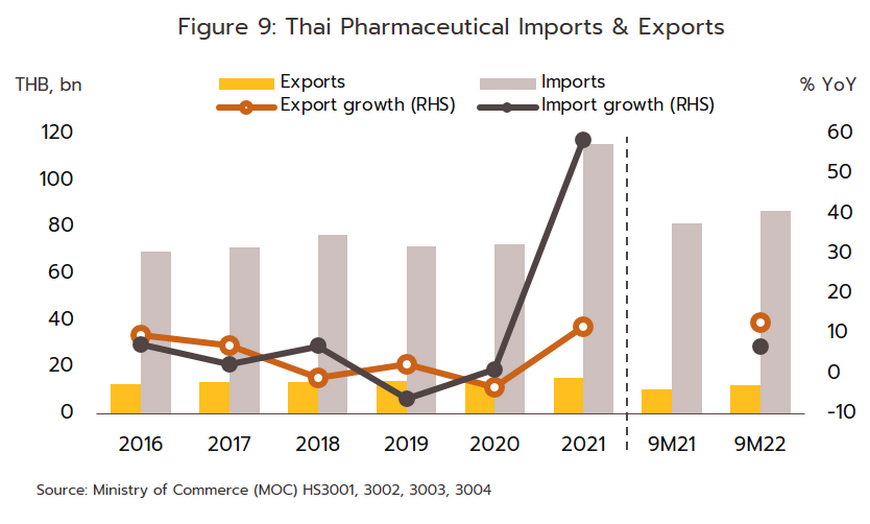

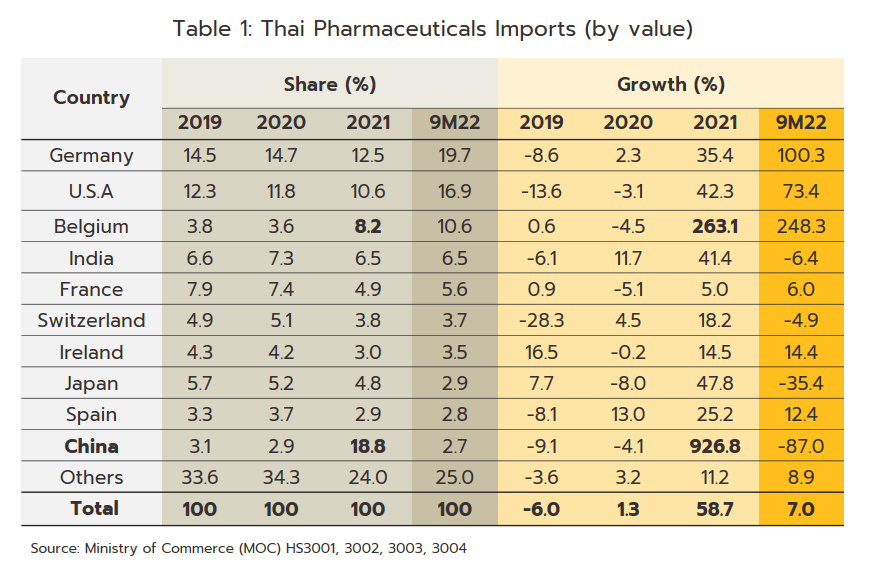

Export market: The value of Thai pharmaceutical exports[4] increased at an average annual rate of 5.1% over the years 2014 to 2020, though because these are generally of low-value generics, this represented just 0.2% of the value of all national exports. Overseas sales are largely to countries in Southeast Asia, and so almost 60% of overseas sales are to Myanmar, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Lao PDR. The extended COVID-19 pandemic benefited Thai exports of pharmaceuticals, especially of vaccines[5], which in 2021 accounted for 12.9% of all pharmaceutical exports by value, up around 2.0% annually. In contrast, imports are mostly of high-cost goods that cannot be manufactured domestically, such as anemia treatments, antibiotics, and cholesterol-lowering drugs, and pharmaceutical imports thus account for 1.0% of all imports to Thailand. These most often come from Germany, the US, and India, from which Thailand is importing an increasing volume of cheap generics (Share of drug imports from India has risen to 8.4% of the total by value, from 5.9% in 2013); India benefits from advantageous patent licensing laws that allow it to produce low-cost generic versions of original drugs, and the Thai pharmaceutical industry thus runs a permanent balance of trade deficit. However, the shape of the market changed markedly with the outbreak of COVID-19 since this led Thailand to ramp up imports of vaccines from China, Belgium, Germany, the US, and France and so in 2021, vaccines accounted for a full 32.5% of the value of all pharmaceutical imports, up from just 5.4% in 2020.

Private sector pharmaceuticals manufacturers typically face pressure from (i) Imports of cheap drugs from India and China, whose production costs are lower than Thailand’s; (ii) Disadvantages of private manufacturers relative to the GPO in terms of manufacturing and distribution; (iii) The Ministry of Public Health and the Comptroller General Department’s list of reference prices for approved drugs, which is used as a tool to control expenses and set appropriate costs for the purchase of pharmaceuticals by public healthcare providers; (iv) rising manufacturing costs on production in private sector following the implementation of the GMP-PIC/S standards[6]; and (v) appropriate storage and sufficient distribution according to Public Health Ministry’s rules on conventional medicine distribution (effective January 1, 2022).

SITUATION

The worsening state of the pandemic and the steady rise in caseloads through 2021 stoked much stronger demand for products used in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19, including personal protective equipment, vaccines, analgesics and antipyretics, treatments for the respiratory system, vitamins, and traditional herbal cures. One outcome of this was that officials reported a significant jump in the number of businesses connected to the sale of medicines and of medical supplies and equipment, which went from 994 in 2019 to 1,792 in 2021. However, the number of patients seeking treatment in hospitals for non-urgent or non-critical conditions dropped and so demand for many medicines softened, a situation that was amplified by the difficulty Thais and non-Thais had traveling. However, at the same time, pharmacies took on a much more central role linking state services, hospitals, and the public and so although trade came under pressure from the overall weakness in consumer spending power, pharmacies benefited from increased sales to some consumer groups. This trend was particularly noticeable for those with chronic non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, asthma, and mental health conditions, who tended to avoid hospitals for fear of contracting COVID-19 and instead made purchases of medications directly from pharmacies. The overall situation with the pharmaceutical industry through 2021 is summarized below.

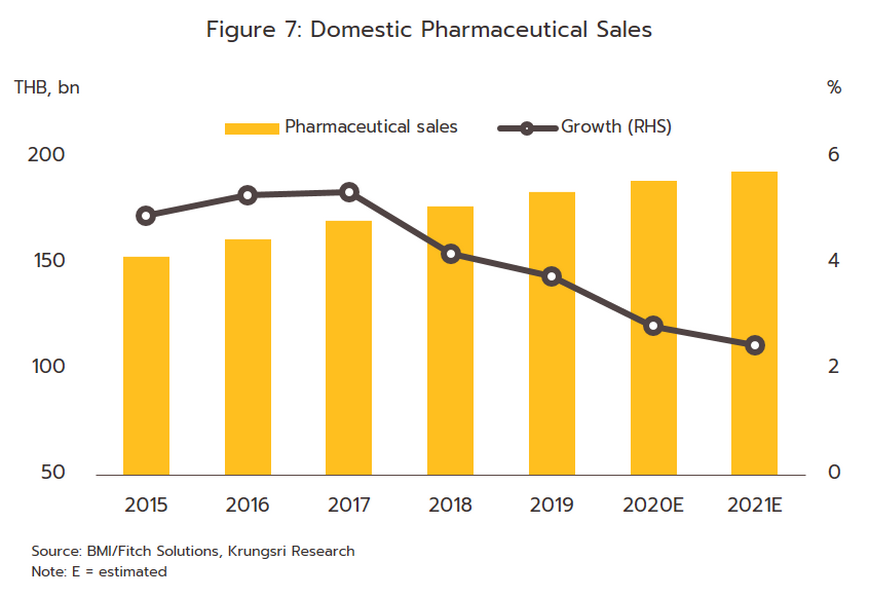

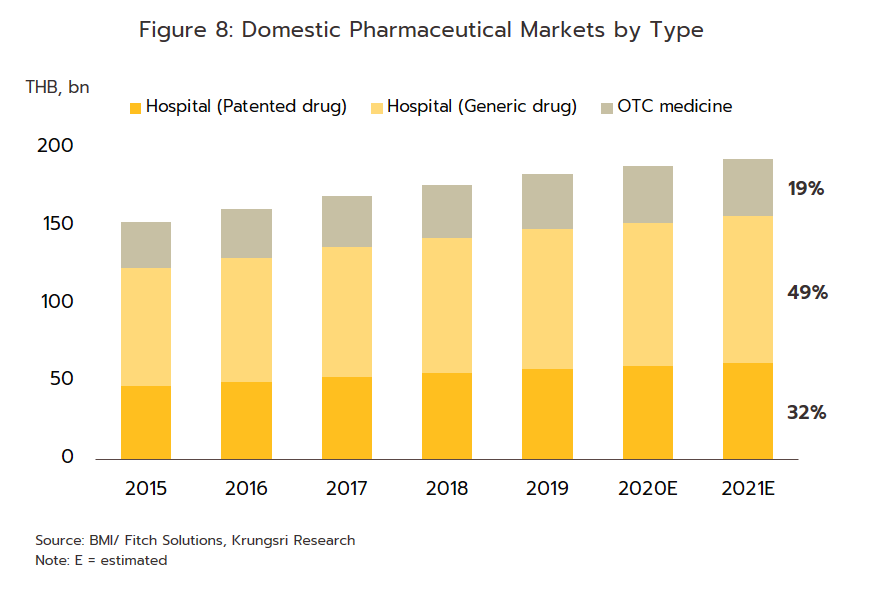

- The value of medicines distributed to the domestic market rose by 2.5% in 2021, and although these generated receipts of THB 193 billion, the rate of growth was down slightly from 2020’s 2.8% (Figure 7). Income was boosted by sales of drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 and of medical equipment such as disposable gloves, blood pressure monitors, and pulse oximeters that were often bought for storage at home, while treatments for non-communicable chronic conditions remained largely unchanged, regardless of the fluctuating outlook for the pandemic. However, sales of medicines to treat one-off or emergency conditions such as antibiotics or medicines for diarrhea or conjunctivitis fell. This was because through the year, people spent more time at home, they wore a mask when in public, and they spent less time in the company of others and so overall rates of infection for these types of condition tended to drop.

1) Prescription drugs and medicines distributed through hospitals, the main domestic market for pharmaceuticals, grew 2.6% YoY. Receipts were split between THB 94 billion from generics (up 2.3%) and THB 62 billion from patented drugs (up 3.2%).

2) ‘Over the counter’ (OTC) distribution through pharmacies rose 1.7% to a value of THB 37 billion (Figure 8). Sales were lifted by changes in government policy that gave pharmacies a more central role in the distribution of medicines, for example by offering incentives to government welfare card holders to buy medicines from pharmacies participating in the ‘Pracharat Blue Flag’ project and by encouraging members of the public treated under the Universal Coverage Scheme to help reduce crowding in hospitals by making purchases in pharmacies instead. Pharmacies have further expanded their role by becoming centers for the provision of services to high-risk groups (with regard to COVID-19 and other diseases), by distributing medicines and advice, and by providing access to services via telephone and mobile applications.

- Domestic output of pharmaceuticals[7] contracted -4.0% YoY to 42,000 tonnes, having already fallen -6.1% in 2020. This decline was driven by the imposition of strict COVID-19 controls that included closing high-risk environments, restricting travel across provincial borders, and preventing large numbers of people gathering together. In addition to this, demand for medicines to treat general illnesses also softened. Thus, production of solutions and liquids, which with a 47.2% share of output was the largest single product group, slipped -2.9%, while output of pills and tablets (31.5% of output), injectables (4.2%) and capsules (3.4%) fell by respectively -6.8%, -22.9% and -2.5%. On the other hand, output of powders (8.2% of output) and creams (5.0%) edged up by respectively 1.2% and 1.0%. Average capacity utilization across the industry also worsened in the year, falling from 56.9% in 2020 to 54.5% a year later. However, as the year closed, output picked up again, and for the last quarter of 2021, production reached 24-quarter high. This turnaround was benefited by the request by the Government Pharmaceutical Office (GPO) that private sector companies licensed for the production of treatments for chronic non-communicable diseases[8] should increase output so that the GPO could then switch its production away from these products and instead start to manufacture the COVID-19 treatment Favipiravir, which began to be distributed domestically at the start of August 2021.

- Export value strengthened 12.0% in 2021 to a total of THB 16 billion (Figure 9) on a surge in demand for vaccines against and treatments for COVID-19, which spread across the region in the year. Exports to the CLMV countries (responsible for a combined total of 56.2% of all export value) rose 8.0% overall, with those to Malaysia (5.2% of exports) +41.6%, the Philippines (5.0%) +8.6%, and Indonesia (4.4%) +156.3%. Given the effects of the pandemic, it is not surprising that exports of vaccines jumped 590% YoY to generate THB 2.0 billion in receipts. This stood against average annual growth of 21.3% over the period from 2016 to 2020. Growth was strongest in markets in Indonesia (up +3,635%, from a background rate of +5.0%), which absorbed 21.4% of vaccine exports by value, followed in importance by the Philippines (up +1,388%) and Vietnam (up +731%). Imports were also increasing strongly in the year, and compared to average growth of 2.5% per year between 2016-2020, the 58.7% jump brought the value of imports to a historic high of THB 116 billion (Figure 9). This sudden increase resulted from a combination of the rising cost of active ingredients and much higher imports of vaccines (e.g., from Sinovac and AstraZeneca), which surged 862% to another historic high of THB 38 billion. Vaccines thus had a 32.5% share of all imports of pharmaceutical goods, having grown at the much more sedate rate of 7.9% over the five years prior to 2020. Including vaccines, imports from China also strengthened by more than 900% to THB 22 billion (Table 1), though considering only Chinese vaccines (50.0% of all vaccine imports by value), the year-on-year increase climbs to over 3,000%. Imports from Belgium were also up 263.1% since this is the home of three manufacturers of COVID-19 vaccines, namely Pfizer/BioNTech, AstraZeneca, and Curevac. Imports from Japan rose 47.8% on strong demand for Favipiravir, while those from the US and Germany were up by 42.3% and 35.4%, respectively.

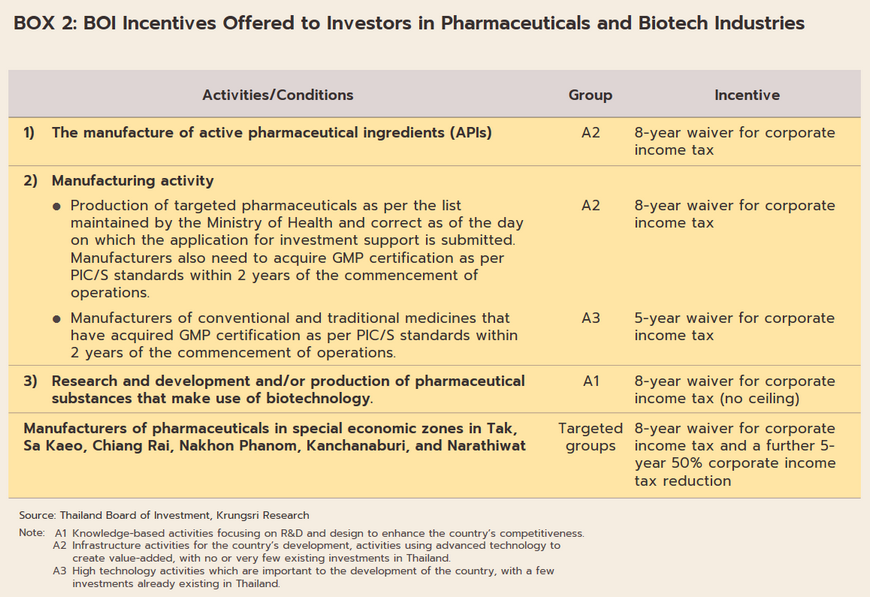

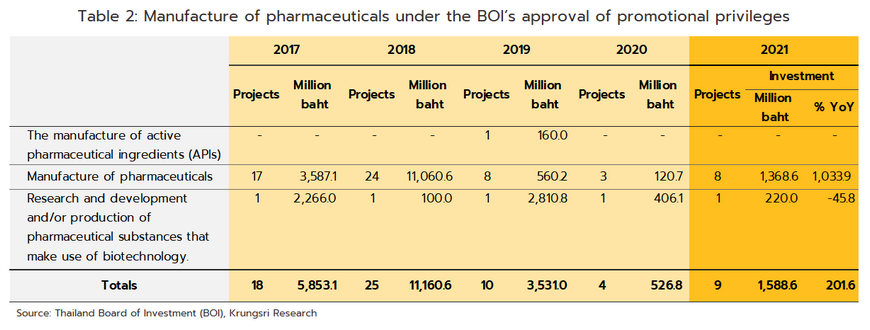

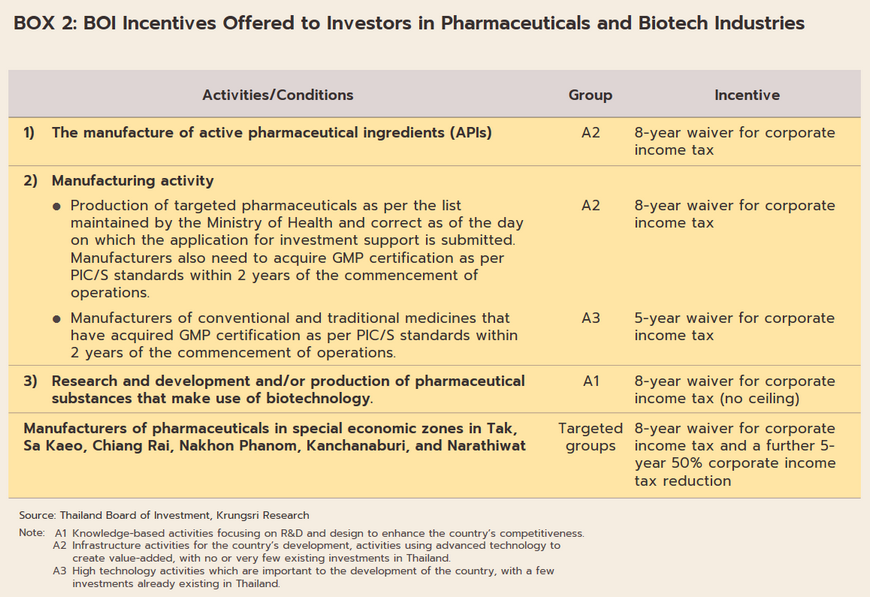

The outbreak of COVID-19 acted as a spur to investment in the pharmaceuticals industry, as reflected in the rise in applications for investment support as per the government’s 2015-2022 policy for investment promotion (Box 2). Thus, in 2021, applications were received for 10 projects with a combined value of THB 1.87 billion, a rise of 238.3% relative to 2020. In the year, applications from 9 projects were approved, the value of these climbing 201.6% YoY to THB 1.6 billion (Table 2), and almost 90% of these were for the production of medicines.

Over the first 9 months of 2022, the domestic market strengthened on a combination of factors. (i) COVID-19 continued to spread and from January 1 to September 30, an estimated 2.45 million new cases were seen. Some of these required hospital treatment, but many made do with home isolation, and so demand for medicines including antipyretics, analgesics, cough medicines, medications for sore throats, vitamins, and herbal medicines remained solid. (ii) The relaxation of pandemic controls allowed economic and social life to return to normal, and with this, patients began to return to hospitals. (iii) With the reopening of the country, tourist numbers have started to rise again, and so for the first time in two years, health tourists and those seeking treatment in Thai hospitals began returning to the country. The consequences of this strengthening of demand are described below.

- Pharmaceutical sales to the domestic market increased for almost all categories. Thus, sales were up 18.1% YoY for tablets and pills (49.5% of the value of the domestic market for pharmaceuticals), 29.2% YoY for liquids and solutions (22.9% of the market), 5.2% YoY for injectables (8.0%), 4.5% YoY for capsules (7.6%), 13.0% YoY for creams (6.8%), and 30.7% YoY for powders (5.3%). Naturally, this also improved the situation with capacity utilization, which climbed from an average of 54.9% in 2021 to 60.0% for 9M22.

- The value of exports also climbed in the period, rising 13.2% YoY to THB 12 billion. Sales from the category of ‘medical treatments and others’ comprised a full 95.6% of the total, and these were up 23.3% YoY. The remaining 4.4% of exports were of vaccines, and over 9M22, sales of these slipped -59.3% YoY. Sales to the CLMV zone (55.7% of total export value) were up 13.1% YoY overall, with those to Malaysia (7.2% of the total), Japan (5.7%), and the Philippines (5.2%) rising by respectively 59.4% YoY, 14.4% YoY, and 32.2% YoY. Alongside this, sales of vaccines to Myanmar and Cambodia rose by 800% YoY and 272% YoY, respectively. Imports increased by 7.0% YoY to THB 88 billion over 9M22, this being partly driven by the decision by the Food and Drug Administration to allow licensed private-sector players to import and distribute COVID-19 treatments (including molnupiravir, favipiravir, and remdesivir) to hospitals. Imports of goods in the category ‘medical treatments and others’ (68.4% of the total) edged up just 0.3% YoY, while those of vaccines (31.6% of the total) climbed 25.0% YoY. Overall imports from the main suppliers of Germany, the US, India, and France (together 48.6% of the total) rose 53.2% YoY. Given the high baseline set a year earlier, imports from China slumped -87.0% YoY.

Looking just at vaccines, imports of these have exploded under the continuing pressure of the COVID-19 pandemic. By value, imports from Germany (29.4% of all vaccine imports) were up 3,631.3% YoY, while those from the US (28.3%) jumped 359.1% YoY thanks to ongoing demand for the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines. However, the abating of the earlier push to source COVID-19 vaccines from China means that the country accounted for just 1.1% of the segment, down from 50.0% in 2021, and these declines have been almost equally strong in terms of volume (-97.6% YoY) and value (-98.1% YoY).

OUTLOOK

The pharmaceuticals industry should see ongoing growth through 2022, helped by demand for medicines and medical supplies that will be boosted by several factors; (i) The effects of the COVID-19 outbreak are lessening and both society and the economy have now largely adjusted to its impacts. As such, life (including the level of economic activity) has mostly returned to its pre-pandemic state. (ii) Spending power will tend to strengthen in line with growth in the economy (Krungsri Research sees GDP growth reaching 3.2% this year, up from 1.6% in 2021) and this will help to bring patients back to hospitals for treatment. However, the effects of this may be limited by the continuing high cost of energy, which has pushed up the prices for goods and services and hence inflation. This will drag on spending power in some consumer groups. (iii) The full reopening of the country from July 1, 2022, will add substantially to tourist arrivals, including those traveling for health reasons. For all of 2022, Thailand expects to welcome 10.4 million visitors, up from just 0.43 million a year earlier. This will then boost demand for medicines, especially in the main tourist areas. In addition to these factors, COVID-19 is now an endemic disease and so large numbers of people will continue to be infected with it, strengthening overall demand for medicines, medical supplies, and vaccines. Krungsri Research thus expects that the value of the domestic market for these goods will grow by some 4.5-5.0% relative to a year earlier. Distribution through hospitals is benefitting from the government’s decision to allow hospitals to secure their own supplies of certain medications (from September 1, this has included favipiravir, molnupiravir and paxlovid). Likewise, pharmacies have also increased their role in the market by becoming providers of healthcare services and by completing doctors’ prescriptions for COVID-19 related medications (over 800 businesses have joined the government’s self-isolation program for non-severe COVID-19 cases, and as of August 29, 55,482 patients with mild symptoms had been treated under this.) Pharmacies are also completing prescriptions for some treatments for non-communicable diseases, including diabetes and hypertension, and over 1,000 companies have joined a scheme to promote the distribution of medicines through pharmacies. Overall, the value of medicines distributed through hospitals and over the counter is therefore forecast to increase by respectively 5.2% and 4.5% YoY.

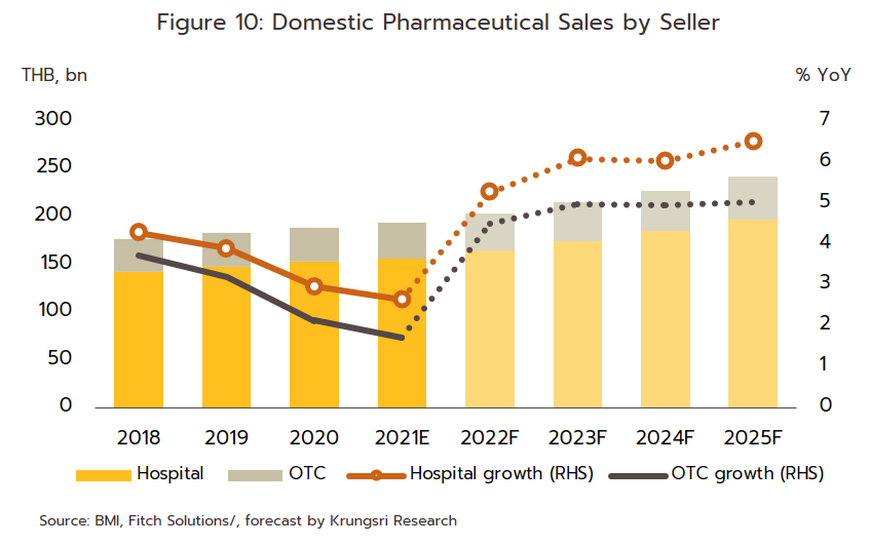

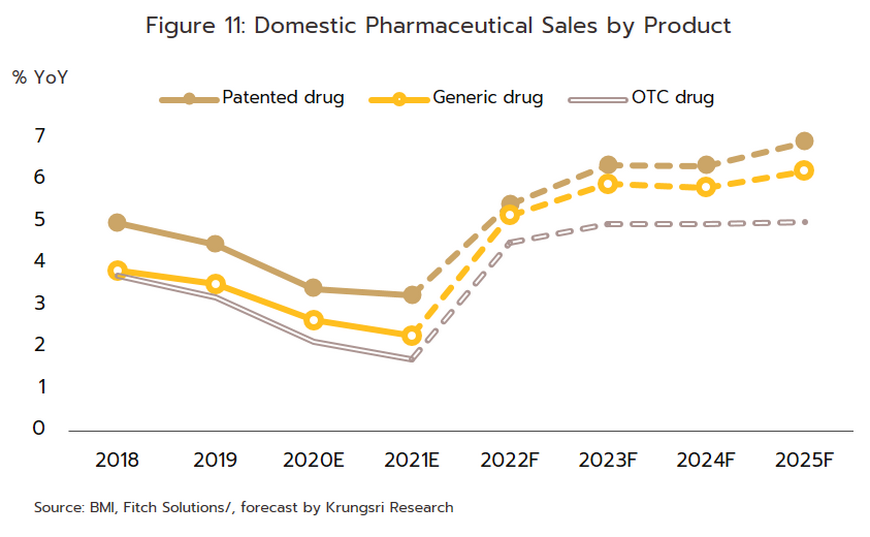

Growth will extend through the period 2023 to 2025 and the domestic market should increase in value by an average of 5.0-6.0% per year (Figure 10). By segment, distribution through hospitals will perform slightly better, growing at the average annual rate of 6.3% (Figure 11), compared to the expected 5.0% growth for OTC distribution. Factors supporting this growth are outlined below.

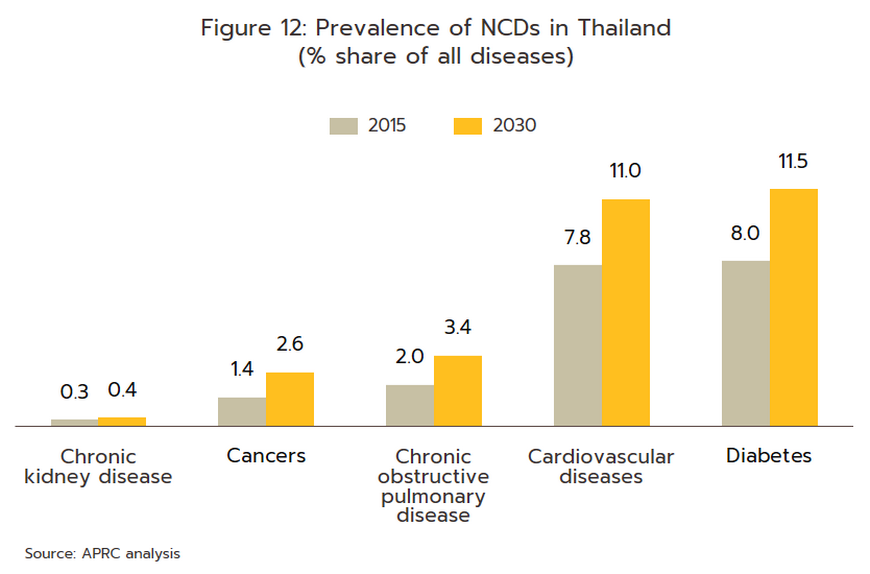

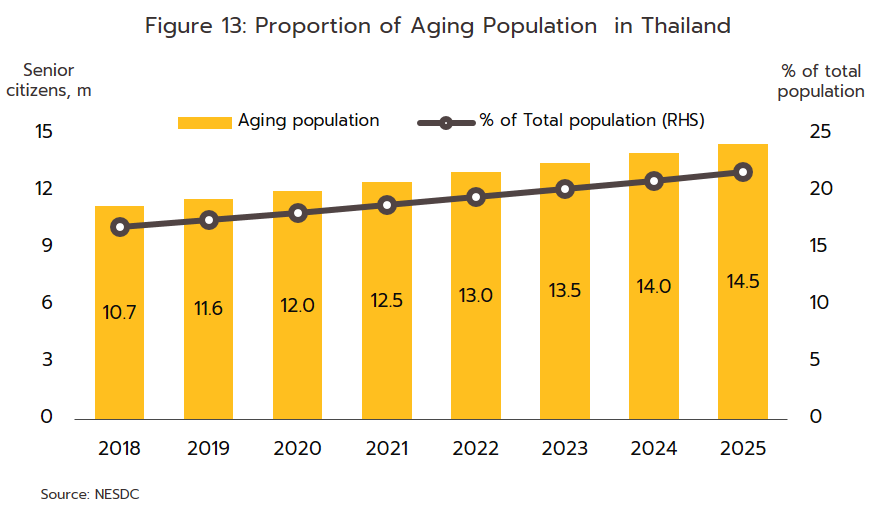

- Rates of illness can be expected to increase for both communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs)[9]. Among the former, the most common are, in order, diarrhea, pneumonia, and dengue fever, while newly emerging diseases[10] will also likely become more common, both at home and abroad. Recent examples of these have included SARS, bird flu, H1N1 influenza (2009), Ebola, Zika, monkeypox/Mpox (cases of which have recently broken out), and of course, COVID-19. In the case of the last of these, Pfizer expects that this will become endemic worldwide by 2024, but with more than 50 major mutations recorded since the disease was first identified, the effectiveness of a double dose of vaccinations has declined significantly. With regard to NCDs, the most common are hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, and strokes (Figure 12). Two principal factors have combined to increase rates of these. (i) Thailand is already an aging society, that is, more than 10% of the population are over 60. This has increased the incidence of conditions such as hypertension (almost half of the elderly in Thailand have elevated blood pressure[11]), diabetes, heart disease, strokes, and cancers. Thailand is now expected to become an aged society (i.e., 20% of the population will be over 60) in 2023 and a super-aged society (i.e., more than 28% of the population will be over 60) by 2033[12] (Figure 13). This will then add to medical bills, and as of 2022, the cost of providing medical care to the elderly has risen to THB 230 billion, or 2.8% of GDP and up from 2.1% in 2010 (source: 12th National Health Action Plan). (ii) Increasing urbanization will mean that an ever-greater share of the population will have to endure a rushed, high-pressure lifestyle lived out in a polluted environment and with only limited opportunities for exercise. This will add to rates of physical and mental ill-health[13]. Indeed, Bangkok has the highest rates of cancer in the country, and at 5%, rates of depression are almost double the national average of 2.7%. Data from the World Health Organization for 2019 indicates that 76.6% of Thai deaths are attributable to NCDs, and this underscores the high and rising demand for medicines, especially for the patented drugs needed to treat more complex conditions.

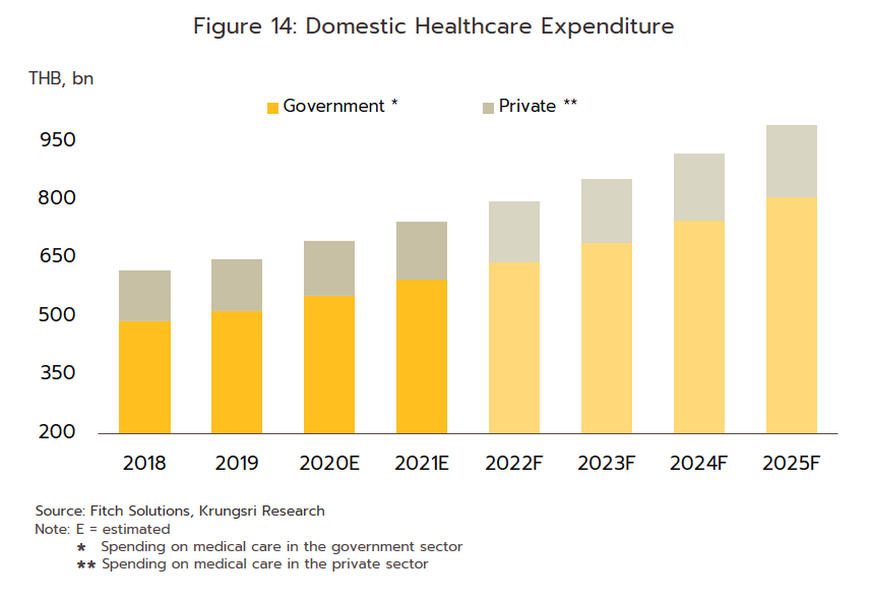

- For the Thai population, access to healthcare services has expanded substantially, and this may now be accessed through the Universal Coverage Scheme/Gold Card (which now covers 71% of the population), social security (18% of the population), and the civil service scheme (8% of the population). Recently, the government has extended the reach of these by including pharmacies among the channels through which healthcare is delivered to the public. This has been achieved through the ‘Pracharat Blue Flag’ project, the program to reduce crowding in hospitals by transferring demand to pharmacies, and an increase in the use of technology to dispense advice on health and medications, the latter including a greater reliance on telemedicine and the deployment of phone apps such as Mor Dee/Good Doctor and Clicknic (for which the userbase rose from 3 million in 2020 to 4 million a year later). Thanks to a combination of the greater convenience that these changes will bring and a wish to reduce the risk of infection, in the future the public are expected to show a much greater tendency to access health services through pharmacies, rather than by visiting a hospital. This will likely be most noticeable for those looking for treatments for NCDs such as diabetes, hypertension, asthma, and some mental health problems. Furthermore, private health insurance take-up is also expanding (coverage rose 10.6% in 2021), and this will add further to demand for products from the pharmaceuticals industry. Given this, for the period 2023-2025, spending on healthcare (medicines and treatments) will expand by an average of 7.6% annually, compared to a rise of 7.0% in 2022. This will be split between increases of 8.1% in the public sector and of 5.7% in the private sector, which compares to rises of respectively 7.6% and 5.3% in 2022 (Figure 14).

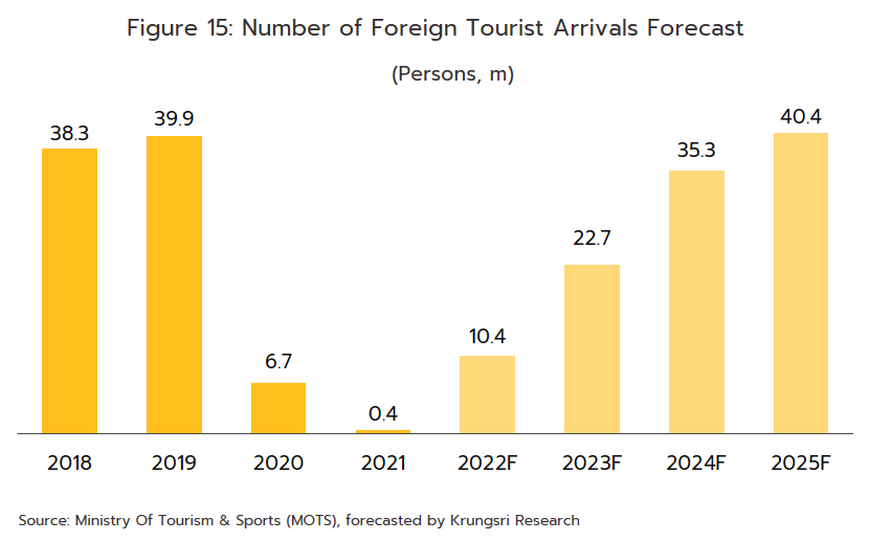

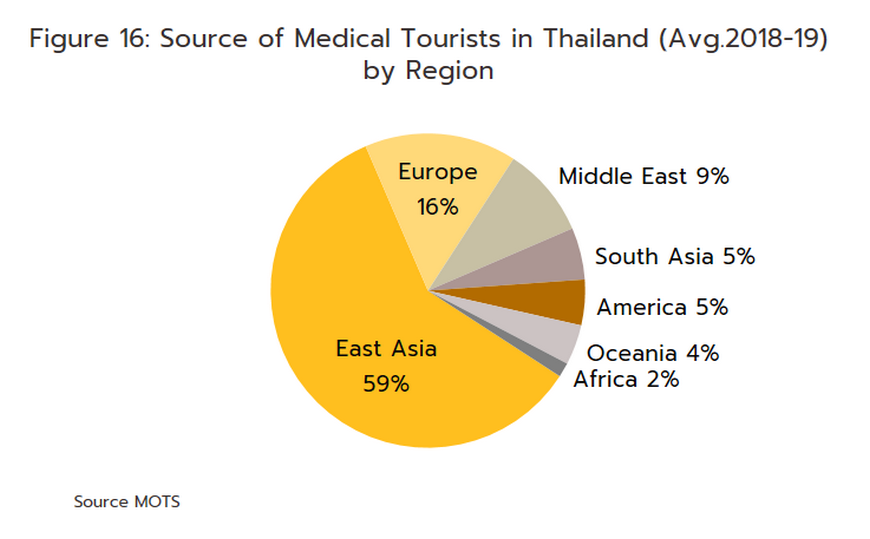

- Foreign patients will return to Thai hospitals in larger numbers over the next few years, and Krungsri Research predicts that foreign arrivals (both regular and medical tourists) will number 22.7 million in 2023, 35.3 million in 2024, and 40.4 million in 2025 (Figure 15). Medical tourists mostly come from East Asia, Europe, and the Middle East (Figure 16), as they are attracted by Thailand’s status as one of the world’s leading providers of medical tourism services. Within this market, Thailand draws particular strengths from the quality of its services, the high standard of the care that is provided, and the lower costs compared to competitors in Singapore and Malaysia. Growth in this market will then add further to demand for pharmaceuticals.

- Demand for wellness and preventive healthcare services and products is also on the rise, though growth in this market was accelerated greatly by the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020. Consumers are thus increasingly changing their regular day-to-day behaviors as they try to avoid ill health, while hospitals and other organizations have also adapted their business strategies to improve health outcomes. This is then likely to support stronger demand for pharmaceuticals and other medical goods, especially for vaccines or products that are believed to boost the immune system such as vitamins, traditional Thai herbal preparations, food supplements, and health drinks. Players already active in the pharmaceutical industry will likely respond to these changes in consumer behavior by introducing or distributing new health products as they look to stake a claim to this rapidly growing market. This outlook is in keeping with work by Euromonitor, which estimates that the global market for health products will expand at an average annual rate of 5.7% over 2021-2025, up from the 3.4% growth maintained over the previous 5 years.

- Continuing technological progress will help to make manufacturing processes more efficient and to expand the public’s access to medical treatments. Thus artificial intelligence and machine learning will help to increase the speed and efficiency of research and development programs; use of big data analytics will help manufacturers rapidly access in-depth information at all stages of the manufacturing process; use of bioreactor systems and low-energy continuous manufacturing processes will maximize output while minimizing wastes; 3D printing will allow players to manufacture human cells or tissue to use in drug development; and 5G technologies will facilitate the development of online platforms and the provision of telepharmacy services, and help to connect pharmaceutical supply chains from upstream manufacturers to downstream consumers (e.g., Medcare). Taken together, this will help to increase the overall ease and convenience of the system, reduce travel and waiting times, and provide easier access to healthcare services, hopefully before any conditions become too serious.

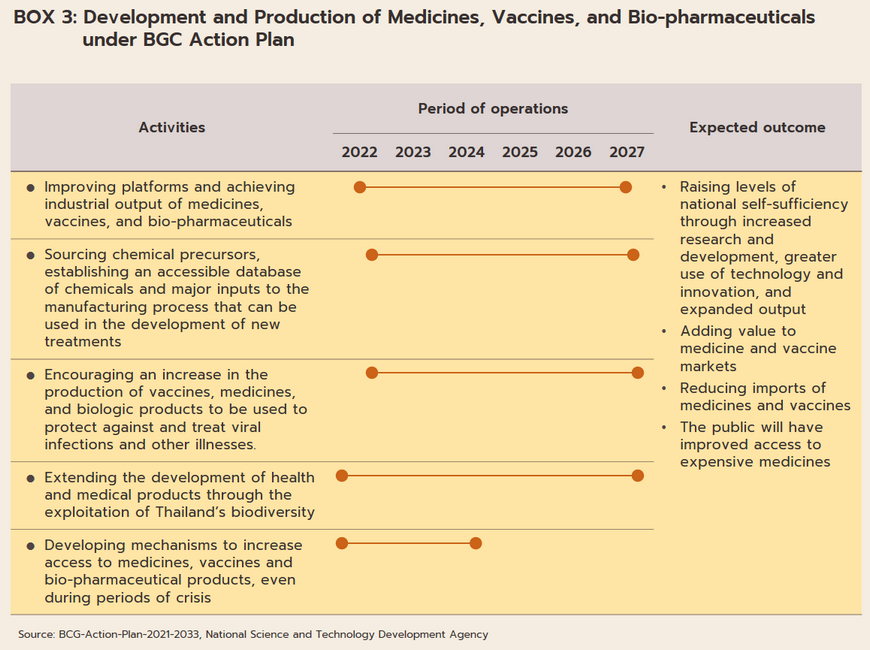

- The industry will in addition benefit from government policy that aims to increase investment inflows into the production of pharmaceuticals. (i) BOI investment promotion schemes (Box 2) aim to stimulate greater investment in the medical and related industries by offering 8-year corporate tax waivers for manufacturers of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and 5-year waivers for general manufacturers of pharmaceuticals. (ii) The pharmaceuticals industry is one of the government’s new S-curve industries in the EEC area, and promotion of the industry should lead to an increase in research and development, which will then help to lower production costs below those of imports, especially for medicines that require high-tech production processes. As part of this, the government is providing funding for R&D and offering further tax breaks (in the first half of 2022, one application was made for investment support for biotechnology-related R&D totaling THB 3.7 billion). (iii) Measures to support the domestic production of pharmaceuticals over 2023-2027 aim at increasing the value of national pharmaceuticals output by THB 100 billion and to grow export markets to a value of THB 13 billion. The motivation behind this is the wish to increase the security of the domestic supply of medicines. (iv) The 2021-2027 strategic plan to shift the economy to the BCG (bio, circular, and green) model (Box 3) will help to increase the output of medical and health goods drawn from Thailand’s natural biodiversity, to increase the added-value in the markets for vaccines and medicines, and to cut imports, thus providing the general public with greater access to high-cost medicines.

The government is also supporting an expansion in the domestic production of both high-value original drugs and those that have come out of patent, such as antibiotics and treatments for high blood pressure and diabetes, as well as medicines developed from biological products (e.g., cancer treatments and vaccines), for which demand is rising. This will help to bolster the strength of domestic pharmaceutical production and reduce reliance on imports. In light of these changes, major players are now increasingly attracted to the industry and numerous plans are underway to build factories for the synthesis of active pharmaceutical inputs and other important materials used in the manufacturing process. The output from these will then be used to produce treatments for major illnesses and diseases. Examples of these developments include the joint venture between PTT and the GPO to build a facility for the production of three types of advanced cancer treatments: (i) chemotherapy drugs (one of the mainstays of cancer treatments); (ii) biosimilar monoclonal antibodies that will be manufactured in the form of tablets and injectables; and (iii) Targeted cancer therapies. This facility is being built in the PTT Wanarom Industrial Estate, also called the PTT WEcoZi Estate, in Rayong. Ground was broken in 2022 and the first treatments produced onsite should reach patients by 2027. SCG Chemicals is also investing in the manufacture of biologic medicals and advanced vaccines by Siam Bioscience, which is developing active ingredients for use in cancer treatments as well as for medicines targeting arthritis, psoriasis, and autoimmune conditions. (Recently, SCG Chemicals partnered with Siam Bioscience and AstraZeneca to produce the AZD1222 COVID-19 vaccine). In addition, the National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC), the National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA), and the Government Pharmaceutical Office (GPO) are cooperating to develop the active ingredients needed for the production of Favipiravir, a chemical used in the treatment of SAR-CoV-2. This chemical is also attracting attention from PTT; the company is currently looking into the possibility of constructing a facility to synthesize the chemicals needed to manufacture this and other in-demand pharmaceuticals, which would then cut dependency on imports.

The overall assessment of the state of Thailand’s pharmaceutical industry and related areas is broadly positive. (i) Thai doctors and biomedical engineers are skilled in medical research, especially with regard to vaccines. (ii) The wide range of Thai herbal treatments[14] means that the country is well placed to use extracts from these as the basis for new biomedical/biopharma products. (iii) Following recent outbreaks of Zika, MERS, Ebola and COVID-19, progress on bioinformatics has significantly improved research on drug development (Box 4). (iv) The transfer of technology from AstraZeneca relating to the production of the COVID-19 vaccine (Thailand has been manufacturing this on a commercial basis since June 2021) means that country was home to the first center for the production of COVID-19 vaccines in the ASEAN zone. Thanks to the combination of these factors, Thailand now has a domestic industry capable of manufacturing high-quality but lower-cost vaccines and bio-pharmaceuticals. This will then help to undercut the country’s future dependency on imports of expensive patented medicines[15] and to further establish the country as the ASEAN hub for the provision of comprehensive medical services.

The Thai pharmaceuticals industry will also face a number of challenges over the coming years. (i) Thailand still lacks security of intermediate supply since the country does not have the domestic ability to manufacture many medicines. Domestic production is thus still widely dependent on imports of (and is largely focused on) the output of generics, while products that depend on high-tech manufacturing processes are almost entirely sourced abroad. (ii) Competition is tending to intensify. (a) Large foreign players have entered the Thai market, though this is generally to use the country as a manufacturing base for the export of finished goods back to their home country or on to other overseas markets. For example, over 2019-2021, 14 applications for investment support schemes worth a total of THB 813.1 million were received from Japanese producers of medical/pharmaceutical goods, up from 2 projects worth THB 347.8 million in 2018. One application was also received in 2018 from a South Korean company for investments worth THB 10 billion. (b) Thai companies that are focused on other parts of the economy (e.g., chemicals, petrochemicals, and energy) are also expanding into the pharmaceuticals industry. (iii) Thai manufacturers’ production costs are tending to climb on: (a) the need to overhaul production processes to meet the GMP-PIC/S standards; (b) the requirement that manufacturers, importers, and retailers of pharmaceuticals need to meet certain standards regarding the storage of medicines and medical equipment; and (c) the rising cost of imports and raw materials. (iv) The possibility of joining the CPTPP (currently under discussion) may have consequences for drug patents[16] since the length of patent protection may be extended to 20 years, which would then add to uncertainty about the price of some medicines.

[1] Under the WTO’s Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

[2] The Drug Act has been enforced since 1967 and was amended. The Drug Act (No. 6) B.E. 2562 has been completed and is enforced.

[3] This includes: (i) modern pharmacies, (ii) pharmacies specializing in the sale of prepackaged drugs that are not subject to controls on their sale, (iii) wholesalers of pharmaceuticals, (iv) importers of pharmaceuticals, and (v) manufacturers of pharmaceuticals.

[4] The import and export of goods with HS codes 3001, 3002, 3003 and 3004.

[5] HS30022020, i.e., vaccines for tetanus, whopping cough, measles, meningitis (spinal and cerebral), polio and others (These accounted for 99% of the value of imports of vaccines in 2021, up almost 800% from 2020).

[6] The Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) is a cooperative framework which was set up by GMP inspectors from a number of countries (but especially European ones) that wished to establish universal standards for assessing GMP in pharmaceuticals production. Thailand officially became its 49th member on August 1, 2016.

[7] Source: The Office of Industrial Economics. This includes liquids and solutions, tablets and pills, capsules, creams, powders, and injectables (for final products only).

[8] This covered 7 products, for which the Government Pharmaceutical Office is the primary producer. These are: (i) simvastatin, which reduces levels of triglycerides and bad cholesterol in the blood; (ii) metformin, a treatment for diabetes; (iii) losartan, a treatment for hypertension that works by relaxing and widening blood vessels; (iv) propranolol, another hypertension treatment; (v) vitamins B1, B6, and B12; (vi) folic acid, a treatment for hemolytic anemia and folic acid deficiency; and (vii) the antidepressant fluoxetine and the antihistamine loratadine.

[9] Source: Ministry of Public Health, 2020 financial year (October 2019-March 2020)

[10] Emerging infectious diseases include: (i) new infectious diseases that have not previously been encountered, for which it takes some time to research and develop treatment plans; (ii) diseases found in new geographical areas; (iii) re-emerging infectious diseases; and (iv) antimicrobial resistant organisms.

[11] Data from the Ministry of Health shows that of Thailand’s 9 million elderly, over 4 million have hypertension and around a further 2 million people have diabetes.

[12] Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council

[13] Health Systems Research Institute Strategic Action Plan for 2022-2026.

[14] The National Master Plan on Thai Herbal Development 2017-2021 added a list of Thai herbs to the National List of Essential Medicines, and allowed hospitals to use herbal treatments to reduce reliance on expensive imported drugs

[15] Annual Thai imports of medicines and pharmaceuticals cost over THB 100 billion, three-quarters of which is for drug treatments and biopharmaceutical products such as vaccines, drugs, and the expensive but versatile cancer treatment Pembrolizumab.

[16] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is also responsible for checking whether generic drugs have a patent protection, in addition to checking for the quality and safety of the drugs that are requested for registration